Coordinate operations and maps in R

This tutorial shows how to do coordinate transformations and conversions in R. It also demonstrates how spatial data can be mapped with ggplot2 and mapview.

Introduction and setup

This tutorial originated while preparing an R-demonstration during a GIS club at INBO on 16 September 2021. (Further material of the GIS club is available here.)

A straightforward approach for transforming spatial data is available in another tutorial. The current tutorial tackles a few extra aspects.

The tutorial assumes you have some pre-existing knowledge:

- Basic knowledge about coordinate reference systems (CRSs) and geodetic datums; see another tutorial and the references and links therein.

- Knowing how to read geospatial files with

sf. There is another tutorial demonstrating some aspects.

In this tutorial we will apply conversions (without datum shift) and

transformations (with datum shift) to sf and sfc objects. In the

background, these operations use the PROJ library.

Let’s load the needed R packages and prepare a more appropriate theme

for mapping with ggplot2:

library(dplyr)

library(sf)

library(ggplot2)

theme_set(theme_bw())

theme_update(panel.grid = element_line(colour = "grey80"))

library(mapview)

Set up input data if needed:

if (!file.exists(file.path(gisclubdata_path, "gemeenten_belgie.shp"))) {

googledrive::drive_download(googledrive::as_id("1-epL-fyKB8eS-WwuZhjsl8uyZYplAqFA"),

file.path(tempdir(), "data_gisclub.zip"))

unzip(file.path(tempdir(), "data_gisclub.zip"),

exdir = tempdir())

list.files(file.path(tempdir(), "data_gisclub"), full.names = TRUE) %>%

file.copy(gisclubdata_path, recursive = TRUE)

}

The code assumes that you have a gisclubdata_path object defined

(directory path as a string).

Joining and mapping polygon layers

For a given municipalities and watercourses dataset, we would like

to append the municipality name to the watercourses by making a spatial

join.

Reading data and trying to join

Let’s read the data file of Belgian municipalities:

path_municipalities <- file.path(gisclubdata_path, "gemeenten_belgie.shp")

municipalities <- read_sf(path_municipalities)

It looks like this:

municipalities

Simple feature collection with 581 features and 3 fields

Geometry type: MULTIPOLYGON

Dimension: XYZ

Bounding box: xmin: 2.541331 ymin: 49.49695 xmax: 6.408098 ymax: 51.50511

z_range: zmin: 0 zmax: 0

Geodetic CRS: WGS 84

# A tibble: 581 × 4

T_MUN_NL Shape_Leng Shape_Area geometry

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <MULTIPOLYGON [°]>

1 ’s Gravenbrakel 0.759 0.0108 Z (((4.095037 50.66599 0, 4.095101 50.…

2 Aalst 0.676 0.0101 Z (((4.054666 50.99444 0, 4.054666 50.…

3 Aalter 0.735 0.0154 Z (((3.41099 51.15987 0, 3.41275 51.15…

4 Aarlen 0.951 0.0148 Z (((5.860749 49.72667 0, 5.860889 49.…

5 Aarschot 0.640 0.00807 Z (((4.927684 51.03717 0, 4.92797 51.0…

6 Aartselaar 0.265 0.00141 Z (((4.401293 51.14814 0, 4.400461 51.…

7 Aat 0.977 0.0163 Z (((3.756864 50.69743 0, 3.757621 50.…

8 Affligem 0.261 0.00229 Z (((4.114181 50.92559 0, 4.115272 50.…

9 Aiseau-Presles 0.393 0.00284 Z (((4.584122 50.43827 0, 4.584458 50.…

10 Alken 0.336 0.00361 Z (((5.275147 50.9102 0, 5.275645 50.9…

# … with 571 more rows

It appears that the points have three coordinate dimensions (XYZ).

However the features have only two useful dimensions:

st_dimension(municipalities)

[1] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[38] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[75] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[112] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[149] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[186] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[223] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[260] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[297] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[334] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[371] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[408] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[445] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[482] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[519] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

[556] 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

Some tools – e.g. spherical geoprocessing – expect XY data. So we will

drop the Z dimension with st_zm(). Meanwhile we select the only

necessary attribute and rename it, using select().

municipalities <-

municipalities %>%

select(municipality = T_MUN_NL) %>%

st_zm()

We perform similar operations on the watercourses dataset. Here, data

are already defined as two dimensions.

path_watercourses <- file.path(gisclubdata_path, "watergangen_antw.shp")

watercourses <- read_sf(path_watercourses)

watercourses

Simple feature collection with 7258 features and 14 fields

Geometry type: POLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: 138050.5 ymin: 201644.5 xmax: 162761.3 ymax: 230509

CRS: NA

# A tibble: 7,258 × 15

OIDN UIDN VERSIE BEGINDATUM VERSDATUM VHAG NAAM OPNDATUM BGNINV

<dbl> <dbl> <int> <date> <date> <dbl> <chr> <date> <int>

1 205462 492073 3 2017-07-05 2021-05-06 3320 nvt 2017-06-20 13

2 179828 488809 2 2015-01-20 2021-05-06 -9 nvt 2014-12-02 4

3 223031 499842 2 2018-03-28 2021-05-06 54710 Kallebeek… 2018-02-27 4

4 267383 462960 2 2020-02-22 2021-05-06 -9 nvt 2020-01-08 4

5 72361 481073 3 2010-11-08 2021-05-06 65101 nvt 2020-06-22 6

6 223073 499879 3 2018-03-28 2021-05-06 -9 nvt 2018-02-27 13

7 72079 480970 3 2010-11-08 2021-05-06 53460 nvt 2016-06-20 3

8 145811 567202 3 2012-11-20 2021-07-07 -8 ng 2012-10-19 11

9 205453 492064 3 2017-07-05 2021-05-06 -9 nvt 2017-06-20 10

10 269842 463401 2 2020-04-22 2021-05-06 -9 nvt 2020-04-03 4

# … with 7,248 more rows, and 6 more variables: LBLBGNINV <chr>, LENGTE <dbl>,

# OPPERVL <dbl>, Shape_Leng <dbl>, Shape_Area <dbl>, geometry <POLYGON>

Note that not all columns are printed. Let’s preview all columns with

glimpse():

glimpse(watercourses)

Rows: 7,258

Columns: 15

$ OIDN <dbl> 205462, 179828, 223031, 267383, 72361, 223073, 72079, 14581…

$ UIDN <dbl> 492073, 488809, 499842, 462960, 481073, 499879, 480970, 567…

$ VERSIE <int> 3, 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 2, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 2, 3,…

$ BEGINDATUM <date> 2017-07-05, 2015-01-20, 2018-03-28, 2020-02-22, 2010-11-08…

$ VERSDATUM <date> 2021-05-06, 2021-05-06, 2021-05-06, 2021-05-06, 2021-05-06…

$ VHAG <dbl> 3320, -9, 54710, -9, 65101, -9, 53460, -8, -9, -9, -9, -9, …

$ NAAM <chr> "nvt", "nvt", "Kallebeekgeul", "nvt", "nvt", "nvt", "nvt", …

$ OPNDATUM <date> 2017-06-20, 2014-12-02, 2018-02-27, 2020-01-08, 2020-06-22…

$ BGNINV <int> 13, 4, 4, 4, 6, 13, 3, 11, 10, 4, 1, 4, 4, 1, 4, 4, 1, 13, …

$ LBLBGNINV <chr> "aanmaak uniek percelenplan\r\n", "bijhouding binnengebiede…

$ LENGTE <dbl> 570.19, 185.33, 1491.01, 307.60, 286.06, 270.32, 48.11, 17.…

$ OPPERVL <dbl> 2492.23, 494.77, 9350.36, 978.46, 432.97, 405.56, 118.29, 1…

$ Shape_Leng <dbl> 570.18844, 185.32549, 1491.01243, 307.59691, 286.06075, 270…

$ Shape_Area <dbl> 2492.22527, 494.77446, 9350.36080, 978.46010, 432.97004, 40…

$ geometry <POLYGON> POLYGON ((141976.5 222453.1..., POLYGON ((142200.6 2050…

We only select some:

watercourses <-

watercourses %>%

select(polygon_id = OIDN,

vhag_code = VHAG,

watercourse = NAAM)

watercourses

Simple feature collection with 7258 features and 3 fields

Geometry type: POLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: 138050.5 ymin: 201644.5 xmax: 162761.3 ymax: 230509

CRS: NA

# A tibble: 7,258 × 4

polygon_id vhag_code watercourse geometry

<dbl> <dbl> <chr> <POLYGON>

1 205462 3320 nvt ((141976.5 222453.1, 141973.1 222449.6, 1…

2 179828 -9 nvt ((142200.6 205085.9, 142197.3 205085, 142…

3 223031 54710 Kallebeekgeul ((146874.6 203777.1, 146879.3 203775.9, 1…

4 267383 -9 nvt ((148997 209136.1, 148996.7 209136.1, 148…

5 72361 65101 nvt ((141780.9 213697.8, 141780.7 213695.3, 1…

6 223073 -9 nvt ((144377.8 205161.2, 144408.7 205152.8, 1…

7 72079 53460 nvt ((140094.1 210962.7, 140093.8 210962.5, 1…

8 145811 -8 ng ((149004.6 209659.9, 149002.5 209666.4, 1…

9 205453 -9 nvt ((139682 225241.4, 139697.5 225222, 13971…

10 269842 -9 nvt ((155762.1 207273.7, 155766.5 207273, 155…

# … with 7,248 more rows

In the above prints of the municipalities and watercourses objects,

you could already see their coordinate reference system (CRS). With

st_crs() you can extract the crs object; it is printed as:

st_crs(municipalities)

Coordinate Reference System:

User input: WGS 84

wkt:

GEOGCRS["WGS 84",

DATUM["World Geodetic System 1984",

ELLIPSOID["WGS 84",6378137,298.257223563,

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]]],

PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

CS[ellipsoidal,2],

AXIS["latitude",north,

ORDER[1],

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

AXIS["longitude",east,

ORDER[2],

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

ID["EPSG",4326]]

The CRS name ‘WGS 84’ can also be returned by

st_crs(municipalities)$Name. As seen from the WKT string, this is a

geographical CRS.

However for watercourses the CRS is missing:

st_crs(watercourses)

Coordinate Reference System: NA

Can we make the spatial join already?

st_join(watercourses, municipalities) %>% try

Error in st_geos_binop("intersects", x, y, sparse = sparse, prepared = prepared, :

st_crs(x) == st_crs(y) is not TRUE

Fortunately, this doesn’t work: st_join() requires its inputs to

belong to the same CRS.

Well, we know that watercourses is in the projected CRS EPSG:31370

(BD72 / Belgian Lambert 72), so we can just update it:

st_crs(watercourses) <- "EPSG:31370"

Since the CRSs are still different, this should not be sufficient for the join.

st_join(watercourses, municipalities) %>% try

Error in st_geos_binop("intersects", x, y, sparse = sparse, prepared = prepared, :

st_crs(x) == st_crs(y) is not TRUE

Indeed!

Let’s transform municipalities to EPSG:31370:

municipalities_31370 <- st_transform(municipalities, "EPSG:31370")

And now…

(watercourses_comm <- st_join(watercourses, municipalities_31370))

Simple feature collection with 7502 features and 4 fields

Geometry type: POLYGON

Dimension: XY

Bounding box: xmin: 138050.5 ymin: 201644.5 xmax: 162761.3 ymax: 230509

Projected CRS: BD72 / Belgian Lambert 72

# A tibble: 7,502 × 5

polygon_id vhag_code watercourse geometry municipality

* <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <POLYGON [m]> <chr>

1 205462 3320 nvt ((141976.5 222453.1, 141973.… Beveren

2 179828 -9 nvt ((142200.6 205085.9, 142197.… Kruibeke

3 223031 54710 Kallebeekgeul ((146874.6 203777.1, 146879.… Kruibeke

4 267383 -9 nvt ((148997 209136.1, 148996.7 … Antwerpen

5 72361 65101 nvt ((141780.9 213697.8, 141780.… Beveren

6 223073 -9 nvt ((144377.8 205161.2, 144408.… Kruibeke

7 72079 53460 nvt ((140094.1 210962.7, 140093.… Beveren

8 145811 -8 ng ((149004.6 209659.9, 149002.… Antwerpen

9 205453 -9 nvt ((139682 225241.4, 139697.5 … Beveren

10 269842 -9 nvt ((155762.1 207273.7, 155766.… Mortsel

# … with 7,492 more rows

Succeeded!

Two things to note here:

st_join()has an argument ‘join’ that defines the type of topological relationship that is used to either join or not join a geometry from the first layer with a geometry from the second. Various so-called ‘binary predicates’ can be used to define this relationship (see?st_join), but the default one isst_intersects(), i.e. an intersection as defined by the ‘DE-9IM’ model of binary geometry relations.- Since several watercourses intersect more than one municipality,

several of them are repeated in

watercourses_comm, each with another values formunicipality.

We chose to make the spatial join in the EPSG:31370 CRS. However, we

can equally do it on a spherical model of the Earth, when using the

geographical coordinates. We expect the resulting joined attributes to

be equivalent. Let’s check:

st_join(st_transform(watercourses, "EPSG:4326"), municipalities) %>%

st_drop_geometry %>%

all.equal(watercourses_comm %>% st_drop_geometry)

[1] TRUE

Mapping

While it has only one attribute and 581 rows, the object size of

municipalities_31370 is relatively large because its polygons have

numerous vertices:

object.size(municipalities_31370) %>% format(units = "MB")

[1] "22.1 Mb"

This makes a simple map take long to render in R (not shown here; just try yourself):

ggplot(data = municipalities_31370) + geom_sf()

For the sake of this exercise, we make a simplified derived object

comm_simpl_31370 with fewer vertices:

comm_simpl_31370 <- st_simplify(municipalities_31370, dTolerance = 10)

Its size is much smaller:

object.size(comm_simpl_31370) %>% format(units = "MB")

[1] "3 Mb"

So it renders faster.

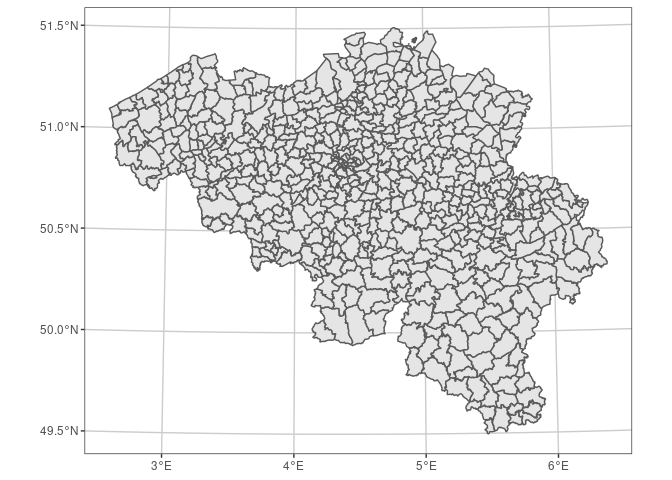

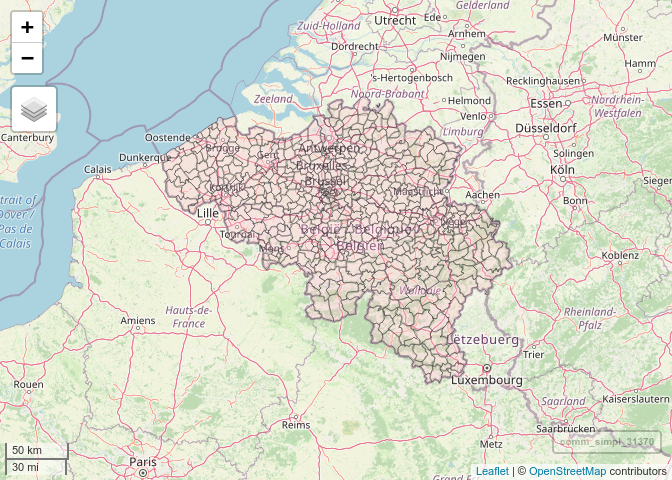

ggplot(data = comm_simpl_31370) + geom_sf()

However, mind that the simplification may be OK for mapping at an appropriate scale, but beware that information has been lost, so shapes have changed and gaps + overlaps will appear between polygons. Hence don’t use this simplified version if you process it further, or for detailed mapping.

Note the latitude-longitude graticule: the map follows the CRS of the plotted object, but the graticule is latitude-longitude by default.

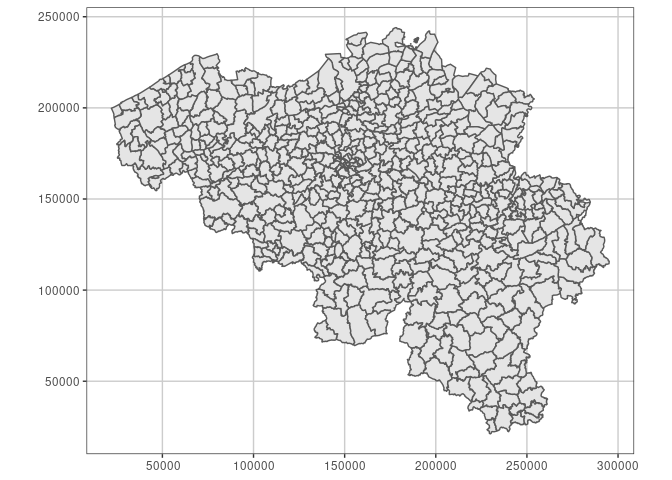

We can plot the graticule of another CRS with coord_sf():

ggplot(data = comm_simpl_31370) + geom_sf() + coord_sf(datum = "EPSG:31370")

The above is the most obvious choice here, since it’s the CRS of the

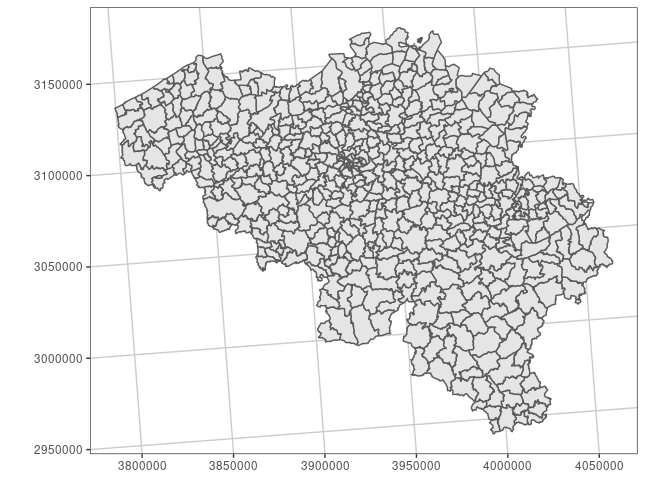

object, but we could as well plot the graticule of e.g. EPSG:3035

(ETRS89-extended / LAEA Europe):

ggplot(data = comm_simpl_31370) + geom_sf() + coord_sf(datum = "EPSG:3035")

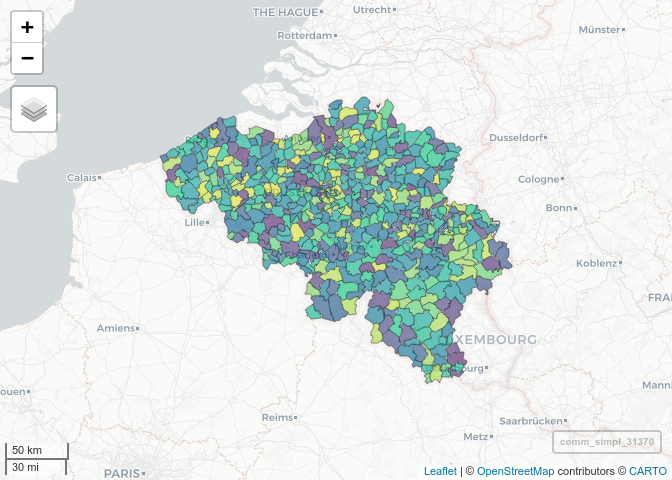

Next to the ggplot2 package, which

we used above, interactive maps can be made with the

mapview package.

Here too, time to render differs between:

mapview(municipalities_31370, legend = FALSE)

and:

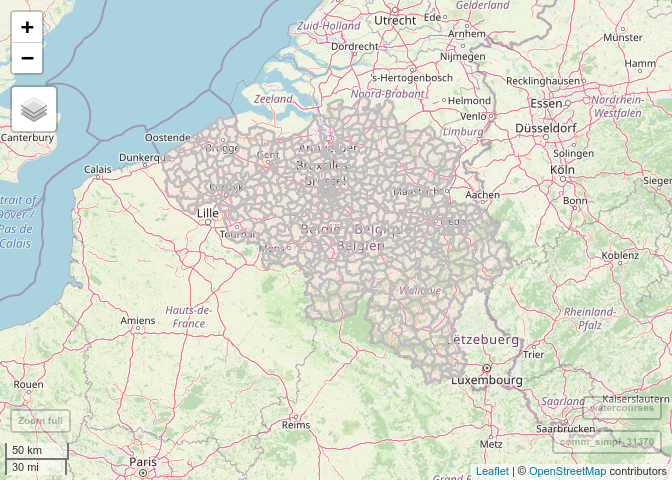

mapview(comm_simpl_31370, legend = FALSE)

Note: run the code to see this and the following interactive maps.

In this case, mapview is using the leaflet package with some nice

defaults, but in the above examples it makes a color map by default

because there’s only one attribute. We don’t want this and we make some

further adjustments:

mapview(comm_simpl_31370,

col.regions = "pink",

alpha.regions = 0.3,

legend = FALSE,

map.types = "OpenStreetMap")

Note that a separate tutorial about leaflet is

available on this website!

Beware that mapview and leaflet produce maps in the ‘WGS 84 /

Pseudo-Mercator’ CRS (EPSG:3857). For that to happen, mapview

transforms spatial objects on-the-fly. Pseudo Mercator or Web

Mercator is a

much used projection in web mapping because the coordinate projection is

computed much faster. However it should not be used in official mapping

or as a projected CRS for geoprocessing, since it has more distortions

(including shape) than e.g. the (truly) conformal Mercator projection

(e.g. in CRS EPSG:3395 – WGS 84 / World Mercator – which is best used

in the equatorial region).

Let’s show two layers with mapview:

mapview(list(comm_simpl_31370, watercourses),

col.regions = c("pink", "blue"),

alpha.regions = c(0.2, 0.5),

color = c("grey", NA),

legend = FALSE,

map.types = "OpenStreetMap")

Different transformation pipelines

We consider a layer of points that correspond to locations where characteristics were determined of Flemish surfacewater bodies:

path_points <- file.path(gisclubdata_path, "meetplaatsen_oppwater.shp")

points <- read_sf(path_points)

Check the CRS:

st_crs(points)

Coordinate Reference System:

User input: Amersfoort / RD New

wkt:

PROJCRS["Amersfoort / RD New",

BASEGEOGCRS["Amersfoort",

DATUM["Amersfoort",

ELLIPSOID["Bessel 1841",6377397.155,299.1528128,

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]]],

PRIMEM["Greenwich",0,

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433]],

ID["EPSG",4289]],

CONVERSION["RD New",

METHOD["Oblique Stereographic",

ID["EPSG",9809]],

PARAMETER["Latitude of natural origin",52.1561605555556,

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433],

ID["EPSG",8801]],

PARAMETER["Longitude of natural origin",5.38763888888889,

ANGLEUNIT["degree",0.0174532925199433],

ID["EPSG",8802]],

PARAMETER["Scale factor at natural origin",0.9999079,

SCALEUNIT["unity",1],

ID["EPSG",8805]],

PARAMETER["False easting",155000,

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1],

ID["EPSG",8806]],

PARAMETER["False northing",463000,

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1],

ID["EPSG",8807]]],

CS[Cartesian,2],

AXIS["easting (X)",east,

ORDER[1],

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

AXIS["northing (Y)",north,

ORDER[2],

LENGTHUNIT["metre",1]],

USAGE[

SCOPE["Engineering survey, topographic mapping."],

AREA["Netherlands - onshore, including Waddenzee, Dutch Wadden Islands and 12-mile offshore coastal zone."],

BBOX[50.75,3.2,53.7,7.22]],

ID["EPSG",28992]]

The points object has the projected ‘Amersfoort / RD New’ CRS

(EPSG:28992), which was created for The Netherlands – onshore. See

e.g.

Wikipedia

for more background about this CRS.

Essentially we are dealing with a different projected CRS than

EPSG:31370. EPSG:28992 uses the ‘Amersfoort’ geodetic datum, defined

using the ‘Bessel 1841’ ellipsoid, while EPSG:31370 has the ‘Reseau

National Belge 1972’ datum, defined using the ‘International 1924’

ellipsoid.1

We will transform points (back) to EPSG:31370 since the data are

outside the intended area of usage. Note that this dataset has been made

for mere demonstrative purposes: since at least a part of the points

fall outside the area of usage (geographic bounding box) of the

‘Amersfoort / RD New’ CRS, the dataset is not appropriate to start from.

But let’s suppose it is all one had available to work with!

Standard approach

By default, the appropriate transformation pipeline (concatenated coordinate operations) can differ between different areas that are represented in a spatial dataset. This is taken care of automatically, based on the bounding boxes of each CRS, but it will also depend on the availability of specific transformation grids.

points_31370 <- st_transform(points, "EPSG:31370")

Notice the completely different coordinate ranges between both CRSs:

st_geometry(points)

#> Geometry set for 7320 features

#> Geometry type: POINT

#> Dimension: XY

#> Bounding box: xmin: -62470.03 ymin: 300542 xmax: 193543.8 ymax: 427302.7

#> Projected CRS: Amersfoort / RD New

#> First 5 geometries:

#> POINT (-30849.68 354341.7)

#> POINT (-31237.91 354683.3)

#> POINT (-28757.74 356391.3)

#> POINT (709.4341 373861.2)

#> POINT (116680.8 340639.1)

st_geometry(points_31370)

#> Geometry set for 7320 features

#> Geometry type: POINT

#> Dimension: XY

#> Bounding box: xmin: 3174.827 ymin: 152992.4 xmax: 260391 ymax: 278347.1

#> Projected CRS: BD72 / Belgian Lambert 72

#> First 5 geometries:

#> POINT (35483.62 205530.5)

#> POINT (35090.55 205866.5)

#> POINT (37545.94 207609.8)

#> POINT (66666.83 225461.1)

#> POINT (183089.2 193870.8)

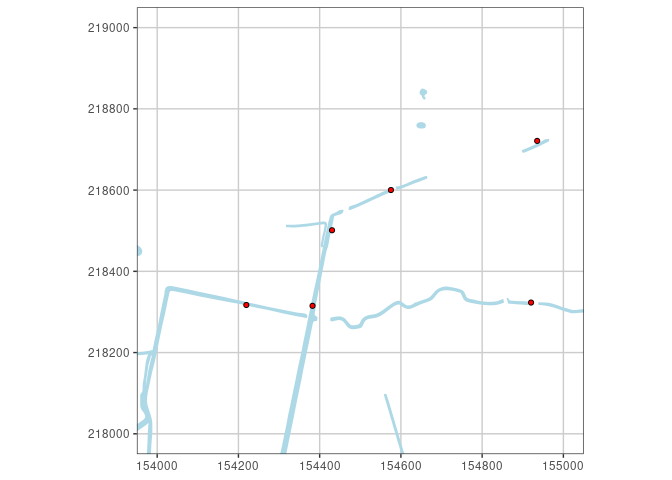

A specific area shown with ggplot2 in EPSG:31370:

ggplot() +

geom_sf(data = watercourses, fill = "lightblue", colour = "lightblue") +

geom_sf(data = points_31370, fill = "red", shape = 21) +

lims(x = c(154e3, 155e3), y = c(218e3, 219e3)) +

coord_sf(datum = "EPSG:31370")

Enforcing a specific pipeline

We can request available transformation pipelines with

sf_proj_pipelines():

pipelines <- sf_proj_pipelines("EPSG:28992", "EPSG:31370")

One can further limit this by specifying the area of interest (aoi

argument), which we didn’t do here.

It is a dataframe with following structure:

glimpse(pipelines)

Rows: 13

Columns: 9

$ id <chr> "pipeline", "pipeline", "pipeline", "pipeline", "pipeline…

$ description <chr> "Inverse of RD New + Amersfoort to ETRS89 (9) + Inverse o…

$ definition <chr> "+proj=pipeline +step +inv +proj=sterea +lat_0=52.1561605…

$ has_inverse <lgl> TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRU…

$ accuracy <dbl> 0.011, 0.201, 0.260, 0.450, 1.001, 1.250, 2.000, 2.000, 2…

$ axis_order <lgl> FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, F…

$ grid_count <int> 2, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

$ instantiable <lgl> TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, TRU…

$ containment <lgl> FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, FALSE, F…

Some metadata about the pipelines:

pipelines %>%

as_tibble %>%

select(definition, description, grid_count, accuracy, instantiable)

# A tibble: 13 × 5

definition description grid_count accuracy instantiable

<chr> <chr> <int> <dbl> <lgl>

1 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 2 0.011 TRUE

2 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 1 0.201 TRUE

3 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 1 0.26 TRUE

4 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 0.45 TRUE

5 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 1 1.00 TRUE

6 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 1.25 TRUE

7 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 2 TRUE

8 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 2 TRUE

9 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 2 TRUE

10 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 2 TRUE

11 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 6 TRUE

12 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 6 TRUE

13 +proj=pipeline +step … Inverse of RD New + … 0 NA TRUE

We can see that the first one has best accuracy. Several pipelines are based on one or two grids for a better accuracy.

When printing the pipelines object, its first row is printed in a more

readable manner:

pipelines

Candidate coordinate operations found: 13

Strict containment: FALSE

Axis order auth compl: FALSE

Source: EPSG:28992

Target: EPSG:31370

Best instantiable operation has accuracy: 0.011 m

Description: Inverse of RD New + Amersfoort to ETRS89 (9) + Inverse of BD72

to ETRS89 (3) + Belgian Lambert 72

Definition: +proj=pipeline +step +inv +proj=sterea +lat_0=52.1561605555556

+lon_0=5.38763888888889 +k=0.9999079 +x_0=155000

+y_0=463000 +ellps=bessel +step +proj=hgridshift

+grids=nl_nsgi_rdtrans2018.tif +step +inv

+proj=hgridshift

+grids=be_ign_bd72lb72_etrs89lb08.tif +step

+proj=lcc +lat_0=90 +lon_0=4.36748666666667

+lat_1=51.1666672333333 +lat_2=49.8333339

+x_0=150000.013 +y_0=5400088.438 +ellps=intl

Since the rows of pipelines are sorted by instantiable and accuracy,

it makes sense to designate the printed pipeline as Best instantiable

operation.

It follows that the same information appears when manually selecting and then printing, except for the number of ‘candidate operations found’:

pipelines[1,]

Candidate coordinate operations found: 1

Strict containment: FALSE

Axis order auth compl: FALSE

Source: EPSG:28992

Target: EPSG:31370

Best instantiable operation has accuracy: 0.011 m

Description: Inverse of RD New + Amersfoort to ETRS89 (9) + Inverse of BD72

to ETRS89 (3) + Belgian Lambert 72

Definition: +proj=pipeline +step +inv +proj=sterea +lat_0=52.1561605555556

+lon_0=5.38763888888889 +k=0.9999079 +x_0=155000

+y_0=463000 +ellps=bessel +step +proj=hgridshift

+grids=nl_nsgi_rdtrans2018.tif +step +inv

+proj=hgridshift

+grids=be_ign_bd72lb72_etrs89lb08.tif +step

+proj=lcc +lat_0=90 +lon_0=4.36748666666667

+lat_1=51.1666672333333 +lat_2=49.8333339

+x_0=150000.013 +y_0=5400088.438 +ellps=intl

If you’d like to get even more metadata on the available pipelines,

including the WKT definitions, you can also run PROJ’s

projinfo command line program

from within R if it’s available in your system PATH.

system("projinfo -s EPSG:28992 -t EPSG:31370 --spatial-test intersects -o WKT2:2019")

The default operation returned by PROJ’s projinfo, based on the

union of the source and target CRS’s bounding box, appears to be just

one pipeline with so-called ballpark

accuracy.

It’s obtained by dropping the --spatial-test intersects option (or

replacing intersects by contains, which is default)2, and so it

matches the pipeline where accuracy equals NA in our pipelines

dataframe:

pipelines[13,]

Candidate coordinate operations found: 1

Strict containment: FALSE

Axis order auth compl: FALSE

Source: EPSG:28992

Target: EPSG:31370

Best instantiable operation has only ballpark accuracy

Description: Inverse of RD New + Ballpark geographic offset from Amersfoort

to BD72 + Belgian Lambert 72

Definition: +proj=pipeline +step +inv +proj=sterea +lat_0=52.1561605555556

+lon_0=5.38763888888889 +k=0.9999079 +x_0=155000

+y_0=463000 +ellps=bessel +step +proj=lcc

+lat_0=90 +lon_0=4.36748666666667

+lat_1=51.1666672333333 +lat_2=49.8333339

+x_0=150000.013 +y_0=5400088.438 +ellps=intl

The low accuracy of a ballpark transformation is because datum differences between source and target CRSs are neglected:

It does not attempt any datum shift, hence the “ballpark” qualifier in its name. Its accuracy is unknown, and could lead in some cases to errors of a few hundreds of metres.

(Source: https://proj.org/glossary.html#term-Ballpark-transformation)

With st_transform() we can enforce a specific pipeline. Note that it

is only available for sfc objects, not sf objects.

Let’s apply the most accurate pipeline to all points:

# We select the pipeline with lowest accuracy (< 0.02), by filtering on accuracy.

# If the grids are installed, this should match the first line of the pipelines object.

chosen_pipeline_definition <- pipelines %>% filter(accuracy < 0.02) %>% pull(definition)

points_31370_strict <-

st_transform(st_geometry(points), "EPSG:31370",

pipeline = chosen_pipeline_definition) %>%

st_sf(st_drop_geometry(points), geometry = .) %>%

as_tibble %>%

st_as_sf

And compare:

st_geometry(points_31370)

#> Geometry set for 7320 features

#> Geometry type: POINT

#> Dimension: XY

#> Bounding box: xmin: 3174.827 ymin: 152992.4 xmax: 260391 ymax: 278347.1

#> Projected CRS: BD72 / Belgian Lambert 72

#> First 5 geometries:

#> POINT (35483.62 205530.5)

#> POINT (35090.55 205866.5)

#> POINT (37545.94 207609.8)

#> POINT (66666.83 225461.1)

#> POINT (183089.2 193870.8)

st_geometry(points_31370_strict)

#> Geometry set for 7320 features (with 9 geometries empty)

#> Geometry type: POINT

#> Dimension: XY

#> Bounding box: xmin: 18976.03 ymin: 152963.3 xmax: 260391 ymax: 244024

#> Projected CRS: BD72 / Belgian Lambert 72

#> First 5 geometries:

#> POINT (35393.39 205495.3)

#> POINT (35000.39 205831.3)

#> POINT (37455.41 207574.3)

#> POINT (66666.83 225461.1)

#> POINT (183089.2 193870.8)

Notice the 9 empty geometries in case of points_31370_strict!

What is happening?

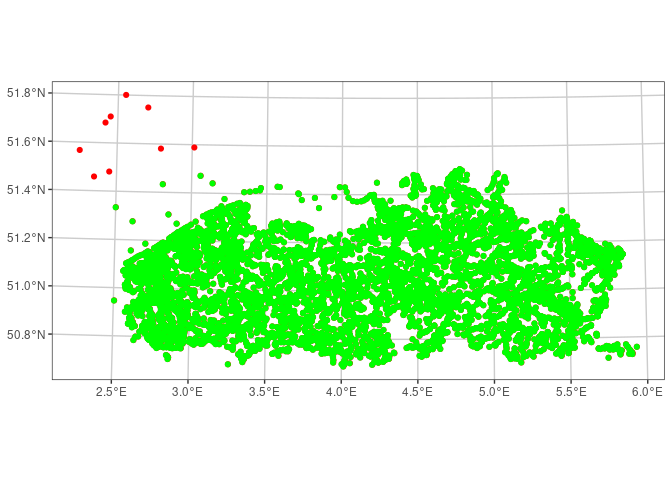

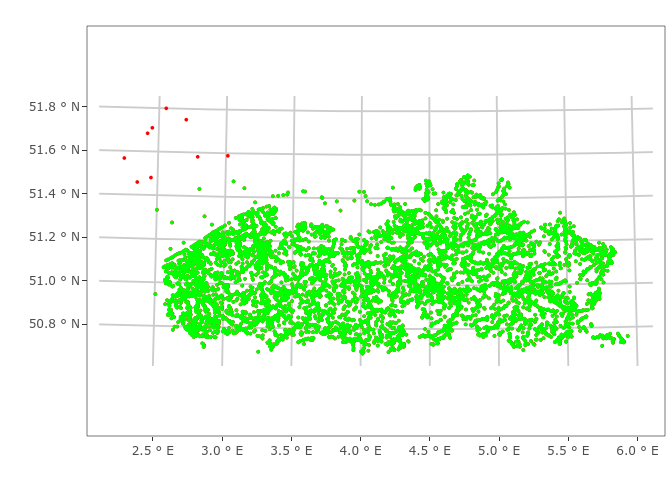

p <-

ggplot() +

geom_sf(data = points_31370, colour = "red") +

geom_sf(data = points_31370_strict, colour = "green")

p

It appears that points too far at sea are considered invalid when applying this pipeline, and their geometry was cleared (although the corresponding row was not dropped).

If we make a zoomable plot, there’s more to discover.

plotly::ggplotly(p)

Most points on the map are on the exact same location between both approaches. We can see that points west and south of the geographic bounding box for usage of the Dutch CRS have a different position depending on the applied approach.

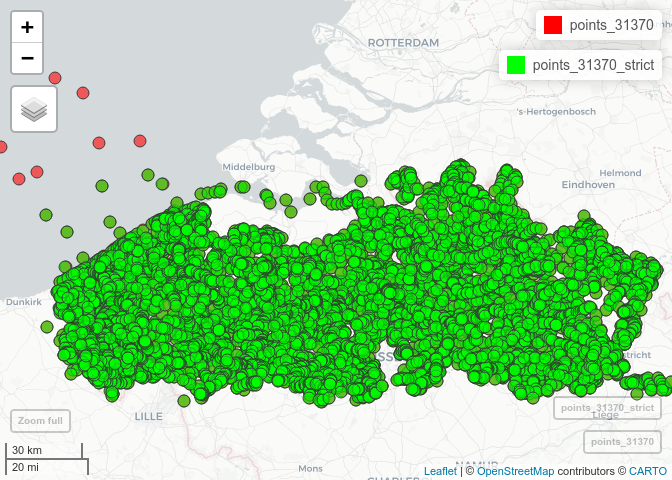

It can be further investigated with mapview (note that this does a

further reprojection to EPSG:3857):

mapview(list(points_31370, points_31370_strict),

col.regions = c("red", "green"))

Here it appears that the western and southern points of points_31370

were transformed with the ballpark-accuracy pipeline: they are way off

the surfacewater bodies!

In this case, one might prefer enforcing the specific pipeline outside

the geographic bounding box of EPSG:28992, as we did for

points_31370_strict. However best explore the other pipelines as well,

e.g. the most accurate one that doesn’t depend on a grid, and consider

using that outside the geographic bounding box.

Bottomline is that you should be suspicious about coordinates outside the CRS’s geographic bounding box! So keep an eye on them when applying a default transformation procedure.

Further reading and more packages

Much more information can be found in the online books by Pebesma &

Bivand (2021)

and Lovelace et al.

(2019). The sf package has a nice

website at https://r-spatial.github.io/sf; version 0.6-1 was

introduced in Pebesma

(2018).

There are several more R packages to make beautiful maps. We

specifically mention tmap

(Tennekes, 2018) and

mapsf for making production-ready

thematic maps. tmap is used a lot in Lovelace et

al.

(2019).

Further, there is the

plotKML package, which

renders spatial objects in Google Earth (Hengl et al.,

2015)!

Bibliography

Hengl T., Roudier P., Beaudette D. & Pebesma E. (2015). plotKML: Scientific Visualization of Spatio-Temporal Data. Journal of Statistical Software 63. http://www.geostat-course.org/system/files/jss1079.pdf.

Lovelace R., Nowosad J. & Muenchow J. (2019). Geocomputation with R. https://geocompr.robinlovelace.net/.

Pebesma E. (2018). Simple Features for R: Standardized Support for Spatial Vector Data. The R Journal 10 (1): 439–446. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2018/RJ-2018-009/index.html.

Pebesma E. & Bivand R. (2021). Spatial Data Science. https://r-spatial.org/book.

Tennekes M. (2018). tmap: Thematic Maps in R. Journal of Statistical Software 84 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v084.i06.

-

Note that several European countries, including Belgium, now provide national projected CRSs that use the common ETRS89 datum (European Terrestrial Reference System 1989). An example is the Belgian CRS

EPSG:3812(ETRS89 / Belgian Lambert 2008). ↩︎ -

In the documentation of

projinfo, we can read about the--spatial-testoption: ‘Specify how the area of use of coordinate operations found in the database are compared to the area of use specified explicitly with--areaor--bbox, or derived implicitly from the area of use of the source and target CRS. By default, projinfo will only keep coordinate operations whose area of use is strictly within the area of interest (contains strategy). If using the intersects strategy, the spatial test is relaxed, and any coordinate operation whose area of use at least partly intersects the area of interest is listed.’ ↩︎